Thoughts

A collection of shorter musings that don’t warrant full blog posts. Click on any item to expand and read.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve heard a variety of creative explanations for why working in the finance industry is a potentially praiseworthy pursuit:

- Your research might be read by policymakers and guide them to run economies better

- You’re enabling price discovery to happen, and the truth to shine forth

- You’re helping pension funds have enough cash to underwrite well-deserved retirements to teachers and doctors and nurses

- You’re providing liquidity to markets and ensuring people can buy or sell securities when they want to

None of these is very convincing to me. There are many legitimate reasons why one might want to go into finance: high salaries/compensation, rapid feedback from the market about whether you’re right or wrong, smart colleagues, an energising culture (depending on the firm). But unless you are specifically pursuing a well-paid career to give more money to charity, I think it is really very disingenuous to pretend (or imply) that social impact is what drives your choices.

One recurring feature about this particular pattern of motivated reasoning is that people often seem determined to arrive at the conclusion that the industry (or just their part in it) is roughly neutral, all things considered – i.e., not net negative.

It’s never usually clear how this neutrality is assessed – relative to a world where you didn’t go into finance (but presumably someone else just filled the position instead)? Relative to the vastly-different world where we have nothing resembling a finance industry? Using an entirely different method that doesn’t appeal to counterfactuals?

As someone who finds the doing/allowing distinction deeply unintuitive, I claim that it is not of much moral importance whether your job avoids doing harm – it matters far more how the job compares to what else you could be doing.

Suppose I am a biophysicist and know my research will totally cure cancer, but because of my inability to play the academic politics game, I won’t get any public credit or profit. It seems pretty obvious it would be wrong for me to decide I’ll instead work at a high-frequency trading fund, even granting every pro-finance argument above and assuming the industry is “net neutral”.

Aiming to do no harm is like following the clichéd tourist guidance to leave only footprints – yet you can aim a lot higher than to have all the impact of your work washed away as soon as you move on. Build castles; plant seeds; strive to create a legacy rather than treading on this world so lightly you make no marks at all. Mere harmlessness leaves far too much on the table.

See also: Moral Ambition, The Life Goals of Dead People, Scott Alexander on Nietzsche.

Among the many benefits of having interactions within a high-trust environment is that you don’t need to keep generating costly signals of acting in good faith – others will assume it by default. I recently spent >2.5h writing & editing a feedback email that only really needed to take 15min, with all the extra time being consumed by me finding ways to persuade the recipient that I really do want them to succeed, and gathering extremely specific evidence to support my claims (since unfortunately I expect they would otherwise – and perhaps even still – be defensive and non-receptive).

If you can create & sustain a culture where the costs of giving feedback are low, much more of it will be surfaced, and this is a very valuable thing: it’s far easier to filter out unhelpful observations than it is to hear what nobody is telling you.

See also: radical transparency, psychological safety, non-violent communication.

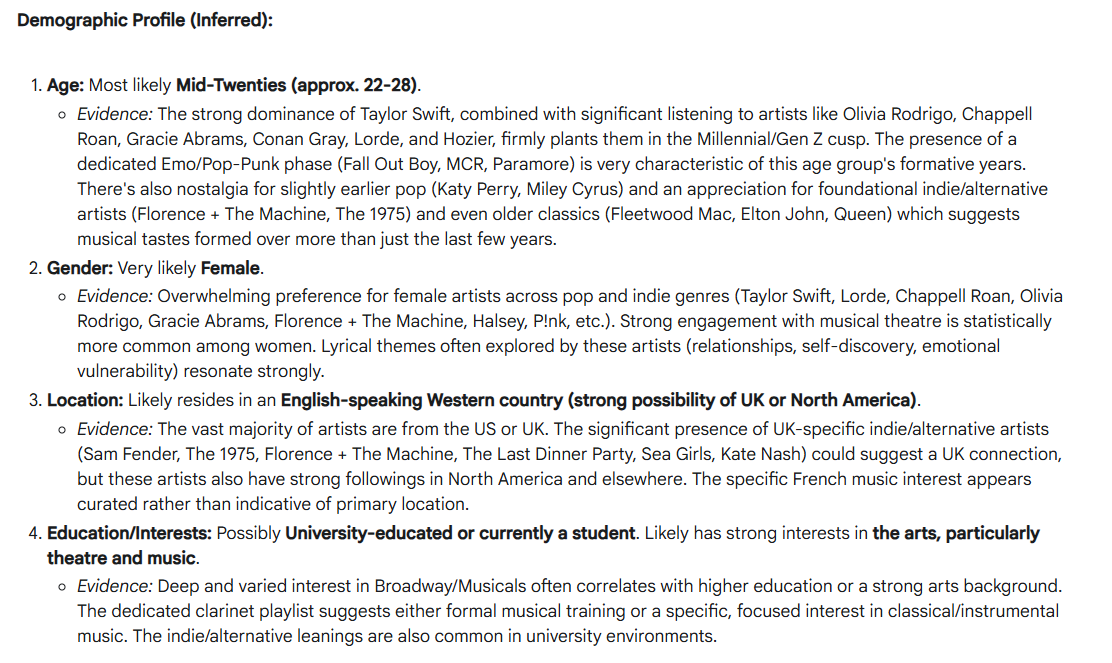

An entertaining new game I came up with, inspired by a rather naively grumbling Jemima Kelly column: paste in lots of your own personal data into an LLM and ask for its best guesses about your demographics & personality (e.g. Big Five traits).

Some examples of data – though carefully consider whether you want this to be available for LLM training, especially if it’s not all your own (e.g. DMs):

- your blog / personal website

- journal entries

- listening / reading / watching history exported from Spotify, YouTube, Netflix, Goodreads, etc

- emails and messages you’ve sent

- list of apps installed on your phone; bookmarks; web browsing history

- LLM chat history

- calendar items; to-do list

- photos of your room décor, fridge contents, wardrobe, bookshelf

- Instagram posts; camera gallery

- things like your Amazon order history, Google Maps timeline, etc., though these feel less whimsical

You could also simply give the LLM your name and get it to use deep research tools, but that spoils things, since it’ll just find your LinkedIn profile and so know all your demographic details.

There’s something quite fun about being at the centre of something else’s attention & analysis (even if you still are the initiator of it), and it’s interesting to see the accuracy of inferences which can be made from relatively publicly-available information. Plus, it gets you thinking about what sorts of rich data you might want to share with other humans to help them get to know you better.

Police in the UK have pretty much given up on dealing with bike theft, to the extent that this is now a standard « progress studies x populism » talking point. I couldn’t quickly find long-run statistics on solving & charging rates for shoplifting or fraud but I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a similar pattern.

There are quite a few other examples of enforcement agencies basically not doing their job:

- It’s against GDPR rules to use “pre-ticked” checkboxes to sign people up for marketing emails, yet these are very common (e.g. Three used them when I registered recently) and I don’t think the ICO does anything to clamp down on it.

- Organisations often fail to respond properly to FOI requests yet the ICO (again…) takes months to investigate even if you do complain.

- Fare dodging on buses in the Bay Area is rampant, with my impression is that there just aren’t any ticket inspectors or others

trying to catch the fare-dodgers

- (I imagine that there are somewhat complicated political things going on here that I don’t fully understand, about Californians’ attitudes to policing.)

- On the metro, installing better fare barriers was associated with violent crime falling 11%. So sorting out the buses would presumably be a good move too.

(There are also many examples of regulatory incompetence, but that’s not quite the thing I’m going for here.)

Why does this matter? Well, it seems like if you’re going to have rules you ought to enforce them, otherwise you’ll be needlessly creating eroding societal norms around rule-following. As described in an excellent piece on the defeat of drunk driving, it’s much easier to successfully stamp out a socially undesirable behaviour once there is a widespread acceptance that it is unacceptable – but that only happens once the incidence of the behaviour is low enough for it to be an exception rather than what is expected. Unfortunately, I suspect that it’s less resource-intensive (and more encouraged by politicians & the media) for regulators / police to use a small number of high-profile punishments as cautionary examples than it is for them to consistently catch and reprimand as many offenders as possible.1 As a result, the vast majority of offenders get away with things completely unimpeded, and the behaviour ends up totally normalised.

24 Apr: this amusing Bagehot column on “banning things harder” pre-empted the latest silly Lib Dem proposal

20 Jun: the discussion above is very closely related to the concept of state capacity. HMRC failing to collect tax owed to it is a prime example of non-enforcement, and my sense is that often this comes about due to authorities not having enough information to work with. Famously, the majority of government revenue in the 18th-19th centuries came from tariffs: states lacked the bureaucratic apparatus to charge direct taxes on income/profits and the political capital (or oversight of businesses) to introduce sales taxes – but they were able to put enough officials at ports to reliably collect customs duties. Even today, informational issues constrain the government’s space of feasible policies: this article made an interesting point about the challenge of accurately valuing businesses & other assets is a significant obstacle to introducing new wealth taxes. There are quite a few enjoyable political economy papers along these lines.

-

See, for example, how infrequent entries on the ICO’s “Enforcement action” page are. ↩︎

The FT has a new feature where you can get a summary of their articles, which comes with this button at the top:

I’d read the wording and the ✨sparkle✨ as hinting that the AI summary will be produced on-the-fly. And these expectations would seem to be confirmed by the animations they use when you load the page and click the button.

But it turns out that this summary has been pre-written, since it was “edited by an FT journalist”!

I’m sure it must have been a deliberate design choice to make it seem like the summary is genuinely generated in response to your click – there’s no reason otherwise why they wouldn’t have just used a simple toggle. (It’s a bit strange why they didn’t realise this would be so transparently misleading, though.)

What makes interactivity so appealing? I think it’s that you get the sense of being in control & writing your own story, which means that things feel like they’re unique. Everyone knows that children like things you can click – every time I went to museums in London as a young child, my favourite place to visit was the energy hall at the Science Museum, because they had the most touchscreens with buttons to press. Seems like the FT has concluded that adults want more of that in their lives too.

Carbon

▼- The emissions from one round trip between London and San Francisco are about 1 tonne of CO2e.

- I’d be perfectly happy to have paid the $200 the Environmental Protection Agency says is the social cost of these emissions and cover the externality I’m imposing on others. I don’t think I’d have paid $1000, which is the figure this paper reaches. (I haven’t looked at it beyond the abstract, and that does feel like a surprisingly high number.)

- That’s about equal to the CO2e from 10kg of beef, or a similar order of magnitude to the GHG effects of a typical Brit’s meat consumption in a year. Alternatively, it’s about 15% of the UK’s yearly consumption-based CO2 emissions per capita (though note that this varies by about a factor of 2 in other sources that I suspect are less reliable but haven’t investigated).

- I’m a bit intuitively suspicious about offsets, plus I’m almost certain that there are more impactful ways to spend my money altruistically, which is why I didn’t in fact buy any.

- I do feel bad about the jet-setting, though, and I’m not totally rational about these things. When I went to Paris recently I took the Eurostar rather than the plane (primarily because I’d have been guilty flying, though there was also a convenience factor). I think it cost about £150 more, but saved less than 100kg CO2e.

Waiting

▼- I don’t fly often enough to benefit from any loyalty programmes, so I chose Virgin because they seemed to have the lowest delay rates.

Frustratingly we were nonetheless 2h delayed leaving LHR, but the plane managed to arrive only 15min late at SFO.

- Miraculously good tailwinds? No, I think just sneaky schedule padding paying off.

- Which raises the question: do people select flights based on travel time? Clearly people have a preference for direct flights above layovers, but my guess is that there’s very little correlation between time and price within the pool of direct flights.

- Maybe this is because the variation in stated times is mostly a function of differences in amount of schedule padding and so pretty much random noise? Or just that people are bad at valuing their time.

- The fact that the amount of schedule padding is growing also suggests that there isn’t much competition between airlines along the speed dimension, for whatever reason.

- Why don’t some airlines voluntarily give delay compensation above the legally required minimum, and compete with other companies with that differentiation?

- I’d happily pay e.g. a 10% premium on each of my flights to be properly compensated for the inconvenience of a 2h delay when it happens, especially since this sets up the right incentives for the airline to be less incompetent and thus probably reduces delays.

- The same is true about trains: it’s frustrating that there’s basically no consequence for train companies to consistently run services 10min late (since Delay Repay only kicks in from either 15min or 30min), and also that the measly 25-50% refund you get on tickets (especially commuter services which are <£10) is substantially less than the time cost of wasting 30min, even using the minimum wage as the value of time.

- Miles observes: “It’s odd to me that you can’t insure yourself privately against [transport] delays. Government mandated delay repay is effectively an insurance scheme where all consumers pay higher fares to receive some compensation if their train is delayed. [People] who place a high value on their time would like to purchase more insurance.”

- In fact, it’s even worse than that – because you have to fill out a form to claim your money back, we should expect that the ones actually receiving the compensation are those who place a lower value on their time! (This isn’t a terrible thing, because those people are probably worse-off and so effectively Delay Repay is functioning like some additional social security. But it’s not really what it’s meant to be for…)

- Getting onto the plane as late as possible seems obviously the right move to me, yet hardly anybody does it – in fact, there’s normally a rush of people

getting up as soon as their group starts boarding.

- This seems to happen with Americans as well as Brits, so I don’t think it’s a worship-the-queue phenomenon.

- The gate is a much nicer place to sit than in the plane!

- (My strategy did backfire once, where the overhead lockers ran out of space going from SFO to BOS and I had to put my suitcase in the hold)

See also: Nate Silver and Zvi on airport efficiency-maxxing.

Busyness

▼- There are child-free hotels and restaurants and pubs, why not flights? I’m sure people would pay a premium to avoid the risk of

sitting in the same cabin as a crying baby for 10 hours.

- If I paid for first-class seats and someone had their child with them there, I’d be infuriated!

- The Virgin flight I took was 1/3 empty in economy, which surprised me – I wouldn’t have thought that

could be profitable.

- The £75 I spent on booking window seats to enjoy the view was wasted, since I ended up moving into the middle to have a whole row to myself (on both flights!). The left-hand side of the plane definitely was better for the view into SFO; I can’t tell whether this site just randomly generates its recommendations or actually is grounded in some facts. (There are also more ordinary listicles like this).

- More planes should get Starlink. Being charged extra for the extremely patchy WiFi is annoying (but I guess makes sense economically), it’s not like they itemise billing for the food & drink you consume.

- Speaking of, I vaguely remember BA having a snack bar in the galley, which I missed on Virgin – I think overall their food was worse and had less generous portions. It’s cool how on United flights the on-screen displays tell you which meals you’ll get and when; other airlines should follow suit.

It’s very easy for me to signal to a company that I’m not interested in buying a product of theirs – I just don’t buy it. Since the company gets the sales data “for free” from stocking the item, they can remove unpopular items from sale without putting in much effort to surveying consumers for their tastes, or similar.

On the other hand, it’s much harder to communicate to them that they’re failing to stock something that I’d pay good money for (as I would’ve liked to while trying and failing to buy some frozen soya beans and vegan mayonnaise in Oxford). In an earlier era I might go chat to the store manager, but nowadays I expect that the shop staff don’t have anything to do with what gets ordered in (except at small family-run convenience stores and suchlike).

This generalises to other products and services. What things are out there that nobody has picked up on the latent demand for?

(Title inspired by a famous book about startups by Peter Thiel called Zero to One.)

Added on 14 Apr: projecting demand for new infrastructure projects is a great example of this challenge.