One potential failure mode of automating AI safety research (i.e., using existing models to align and monitor subsequent ones) is that the models we try to use for that purpose are misaligned, and actually end up sabotaging our work.

These sabotage strategies could be insidious – for example, the model doing a sloppy job of monitoring even if it’s capable of performing better – or more brazen – e.g., secretly inserting vulnerabilities into the code it writes for future models to exploit. Perhaps we try to remove these behaviours and train the models to be genuinely helpful by applying reinforcement learning (RL) that rewards effective monitoring and useful safety research. But this countermeasure could itself fail: a misaligned model might fight back by “exploration hacking” – deliberately avoiding exploring the actions it thinks we’ll reward. The RL training would be ineffective as a result (since there wouldn’t be any high-value actions identified for it to reinforce), allowing the model to continue undermining our safety research.1

Buck Shlegeris has previously written about the similarities (and differences) between AI risk and human insider risk, which largely relate to the blatant sabotage threat model. And it’s easy to see how sabotage by persistent underperformance applies in the human realm – there’s no shortage of anecdotes about employees “quiet quitting” and doing the least work possible without risking reprimand. Here, I want to describe a human analogy for how agents might use exploration hacking to maintain their ability to strategically underperform.

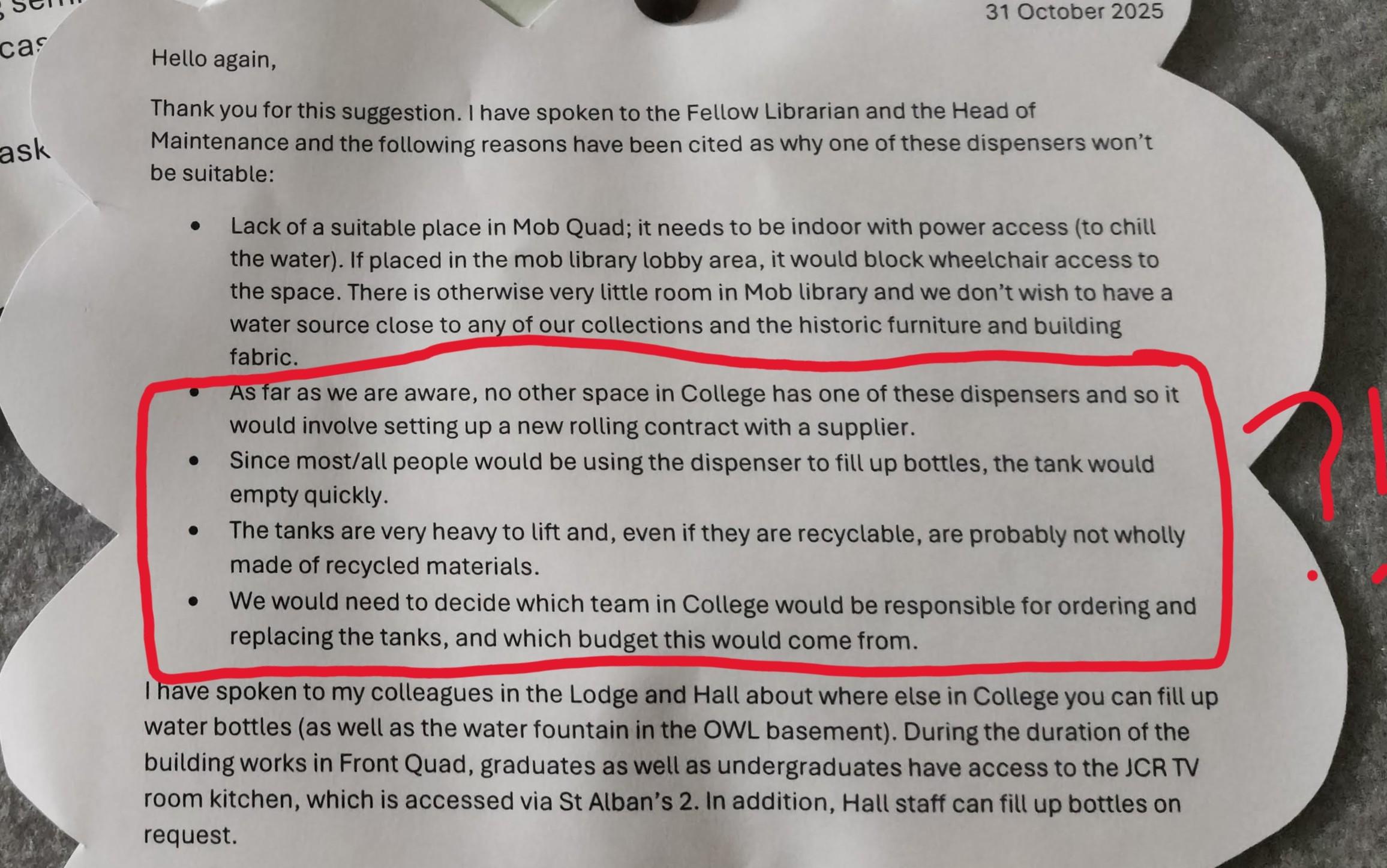

Clearly there are many weighty reasons why a water cooler couldn’t be installed in Merton’s library. Indeed, this was the second neatly-typed explanation of the impossibility of such an endeavour which appeared on the library suggestion board, after I noted that using a bottle-fed dispenser might get around the difficulty of finding a suitable plumbing connection (which was previously cited as the main obstacle).

It’s not as though it took much ingenuity on my part to realise that the plumbing problems could be overcome, nor that the further challenges listed above involve especially hard-to-identify solutions. I’m pretty sure you could generate them with a few minutes of thinking! So it almost seems like the person responsible for replying to my suggestion had deliberately avoided considering potential solutions. You could call it wilful unimaginativeness – or, exploration hacking.2

In the case of a misaligned AI agent we’re trying to deploy for AI safety work, the reasons for engaging in exploration hacking (and sabotage in general) are self-evident. What about for humans? I think it all comes back to incentives, and the fact that at many organisations, no good deed goes unpunished. Realising that a seemingly insurmountable barrier can, in fact, be surmounted will frequently create private costs for the innovative employee without any corresponding benefits – compensation often isn’t performance-linked, but surfacing a solution means that either you have to do the work of implementing it, or whoever else does ends up resenting you for raising the bright idea. Worse still, showing initiative on one occasion creates an expectation (from managers and stakeholders) that you’ll do so again, forcing you to be a more effective operator in future and making the strategic underperformance act harder to sustain.

Like how an RL agent’s avoidance of high-value actions means that it never acquires the capability of interest, this human exploration hacking results in organisations which are less capable than they would otherwise be. And, because managers are some way removed from the problems their direct reports are working on, they may struggle to detect whether an employee is being deliberately unthorough, or faced with a genuinely intractable problem.

Things don’t have to be this way! Some organisations cultivate a culture where, rather than prematurely concluding that a task is impossible and giving up, employees are willing to push ahead with finding novel and creative solutions to issues. This was one of the things I found most exciting about working at Macroscopic: when we really wanted something to happen, we’d put a lot of energy into exploring how we might be able to get there, even if the path seemed circuitous and effortful. As with the AI case, however, you shouldn’t expect human alignment to happen by default – it requires either each agent being enthusiastic about the principal’s mission, or careful incentive design so that it’s in individuals’ self-interests to perform well even if they aren’t fully on board with the terminal goal.

-

If these sound like interesting problems to solve, consider reading more about the field of AI control! ↩︎

-

There are some important disanalogies between the human and AI cases of exploration hacking. Notably, while in the AI case the agent fails to learn, it’s the principal (i.e., the organisation) which fails to acquire the relevant capabilities. But I think this is still an interesting frame to adopt when thinking about how incentives shape individuals' behaviour within larger organisations. ↩︎