Abstract

This essay provides an overview of three key philosophical questions, the answers to which matter greatly for the comparison of competing cause areas within Effective Altruism (EA). These “crucial considerations” are:

-

How bad is death, for the individual dying and for society?

-

How can the goodness of life be measured, and is it better to exist than to not exist?

-

Are humans unique as a species with moral significance, and if not, how much do other species matter?

I argue that it may be impossible to prioritise different cause areas without forming judgements on these three issues, either explicitly or implicitly, and I identify important questions that these considerations are cruxes for. As a result, I suggest that people within the EA community should carefully think through these questions and form their own views on them, avoiding unconscious deference to authority or reliance on instinctive first impressions, just as they would for more empirical crucial considerations.

Introduction

The EA movement is known for its roots in Oxford philosophy,1 but as the community has grown and diversified, there are now many EAs who do not come from an academic philosophical background.2 This essay was prompted in part by conversations I have had with newly-engaged EAs about philosophy. One thing I noticed during these discussions was that, in more than one instance, people had given relatively little thought to high-level philosophical considerations as compared with lower-level empirical ones. I don’t think avoiding philosophical questions is conducive to good epistemics or reasoning transparency, and more importantly, I think it may lead to bad or ill-informed decisions about cause prioritisation.

Just as the heavy-tailed nature of charity effectiveness means that spending enough time to identify the most impactful interventions before taking action is worthwhile, the fact that some problems are much more pressing than others similarly necessitates careful consideration of which to prioritise.3 The most common means of evaluating causes within EA is the importance-neglectedness-tractability (INT) framework. Whilst neglectedness and tractability relate to the availability and efficacy of solutions, the importance of a cause is determined by the value we place upon it, with the judgements we make about this contingent on our own personal beliefs. This means that philosophical fundamentals which would significantly alter the relative sizes of problems (such as by changing your view of the amount of welfare at stake in each one) matter a great deal. I think it therefore makes sense that we should try to examine these underlying questions before diving into the other details of cause comparison – just as it is better to identify the most pressing causes before looking for the most effective interventions.

There are counterarguments to suggest that these philosophical considerations may in fact not be very important for most EAs. One of the stronger objections points to the opportunity cost of over-analysis.4 Encouraging people to spend more time pondering thorny philosophical questions could be harmful if it draws them away from directly impactful work. However, the time cost of this exploration need not be great: I am not advocating for significantly more people to dedicate their careers to global priority research (though 80,000 Hours does list such work as a recommended career path)5, but rather for individuals to spend some time introspecting and reflecting on their considered answers to these philosophical questions. Given the huge variation in pressingness of problems, it seems worthwhile to take at least a little time to explore the important between-cause considerations before selecting one to exploit.6

One separate criticism specific to philosophical considerations is their knottiness: it may be that some philosophical questions do not have decisive answers,7 and as a result, exploring them is a futile time-sink to be avoided. But definitive answers do not necessarily need to be the goal: as Ord and MacAskill’s work outlines, there are ways to make decisions under moral uncertainty, and having more information to base our choices on is better.8 Being explicit and considered in our philosophical fundamentals is preferable to arbitrarily assuming some, even if we are not certain the chosen positions are correct. The process of examining these crucial questions can help clarify our own reasoning, which in turn enables critical comments from others. This can be likened to the importance of attempting a rough estimate when dealing with empirical problems, even if one does not expect the final figure to be accurate. 9

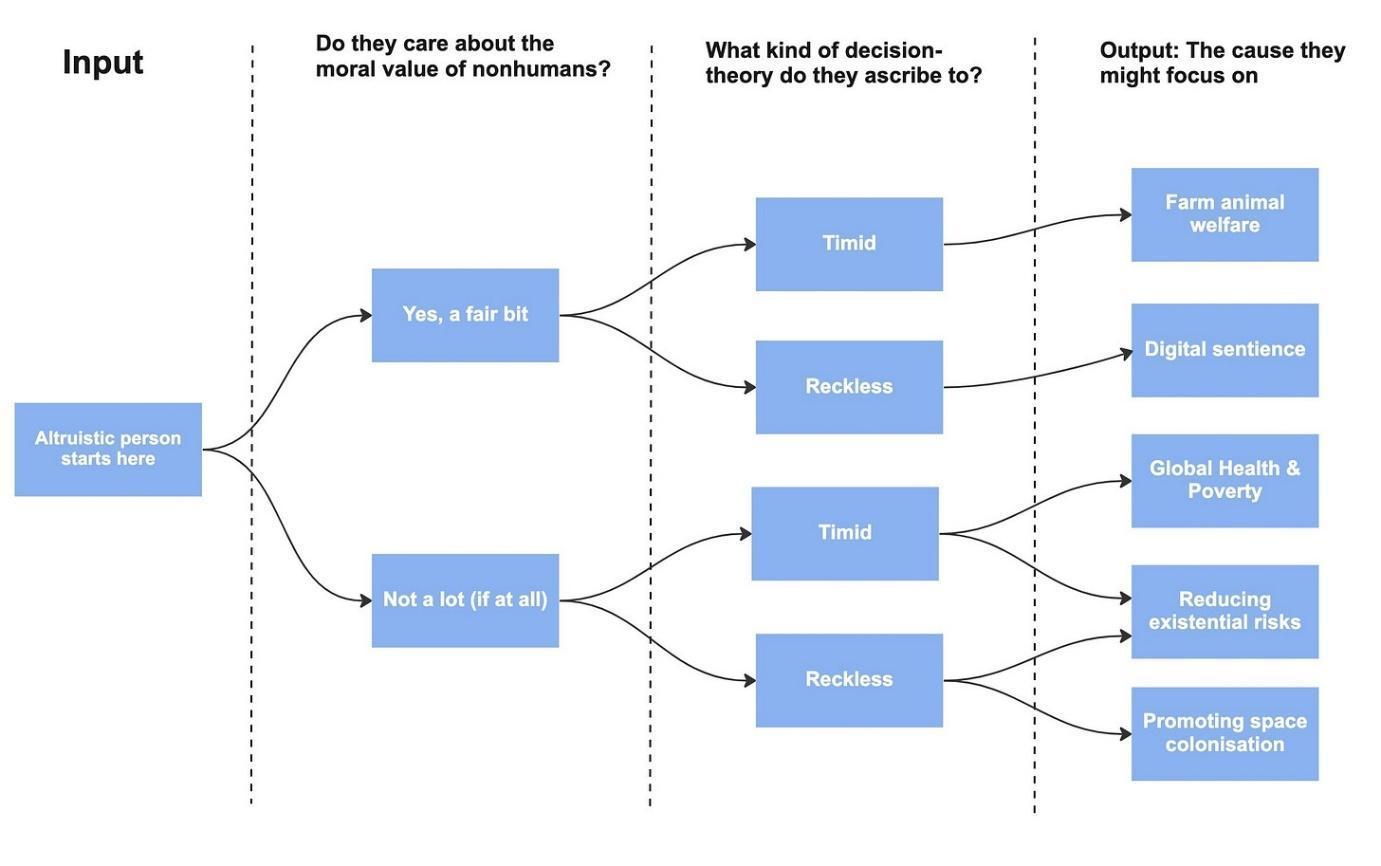

In my conversations with fellow new EAs, I occasionally came across a perception that deep philosophical questions are mostly confected and sit many layers of abstraction away from action-relevancy. Though I imagine this could potentially be true for certain kinds of philosophical puzzles,10 I think it’s mistaken to dismiss philosophical thinking more generally as an indulgent distraction. Aside from one’s choice of value system, around which a significant EA literature already exists,11 there has only been a little research from the EA community directly investigating these fundamental normative questions. Recent work by Ozden (2022) outlined how moral judgements can play a significant role in an individual’s cause prioritisation, with slight changes to often intuition-derived ethical views potentially leading them to focus on an entirely different cause area (see Figure 1 below).12 I build on Ozden’s analysis to identify and explore three key areas of philosophical debate which can be cruxes when one is selecting a cause to work on, namely, death, life, and speciesism.

How bad is death?

The title of Peter Singer’s seminal “The Life You Can Save” is, implicitly, about preventing death.13 Saving lives is a noble thing to do, goes the claim, because the alternative – death – is bad. But is it?

For the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, death could not possibly harm a person. He argued that, since someone’s existence and their death do not overlap in time, death itself is not an experience and therefore cannot be either good or bad. The Epicurean account does not necessarily imply that dying is hedonically neutral: the process itself may well involve pain, which certainly is bad for the living person experiencing it. What Epicurus did argue, though, was that the state of being dead is not itself bad. This alone has important implications: according to Epicurus’s view, if one were to push a button which painlessly ended one’s life, or more prosaically, if one died whilst asleep, nothing bad would have happened.14 For those who believe that pleasure and pain are the only things which are intrinsically good and bad respectively, Epicurus’s conclusion is a fairly compelling one, and we should not dismiss it out of hand.

There are many modern thinkers who strongly disagree with the Epicurean perspective, among them Ord, who argues that it is “not fit to be a guide for action”.15 Ord introduces what is known as the deprivationist account of death: most people would agree that it is worse to die earlier than it is to die later, with this comparative badness stemming from how an individual dying earlier loses out on more of their future.16 Since any death would to some degree deprive a person of goods in their future, dying is worse than remaining alive, goes the argument.17 If the badness of death comes about because of an individual’s forgone future, the implication is that, holding quality of life constant (I discuss this caveat at greater length in the following section), the negatives of death become smaller over time. The old have less in expectation to lose from dying than the young do. The upshot of this would be that we ought to prioritise interventions which prevent the deaths of young people (rather than those who are older), since these avert the greatest amount of bad. Following the argument that earlier deaths are worse leads to the conclusion that the worst possible age to die is when you are a new-born baby. Or should that be, when you’re a foetus? Or embryo? Zygote?

One flaw in the deprivationist account is therefore its vulnerability to the heap-of-sand paradox. If an individual exists at one instant in time and death would be bad for them then, surely it would be even worse a moment earlier. This argument can be made iteratively, culminating in the claim that immediately after conception is the worst time to die – a statement that, intuitively at least, appears shaky. Even if one were to argue that personhood does not exist from conception pinpointing a time at which a clump of cells becomes morally relevant (and thus worth protecting from death) remains difficult due to the heap-of-sand paradox.

There is an alternative view, known as the time-relative interest account (TRIA), which posits that the strength of prudential connection between an individual and their future self should be considered when evaluating the badness of death. The modern population ethicist Jeff McMahan, who introduced the theory, argues that the death of an infant is less bad than that of an adolescent, as the former is “almost entirely cut of psychologically from its own future”.18 The TRIA approach has come under criticism, for instance from Nichols (2011), who demonstrates that it seems to permit, or at least only weakly criticise, infanticide and the killing of adults with Alzheimer’s, and Greaves (2019), who presents several thought experiments which TRIA provides unintuitive answers to.19 Despite these perhaps undesirable implications in edge cases (which McMahan himself admits he accepts with “significant misgivings and considerable unease”), 20 the approach is one of the few practical means available to compare the welfare improvements created by charitable interventions which affect different age groups. For this reason, it is the method adopted in the charity evaluator GiveWell’s “moral weights”, which are used in calculations of cost-effectiveness.21

One’s view on this philosophical issue matters practically. If the death of an unborn infant really is among the worst possible outcomes, efforts to safeguard foetuses (for example, by reducing the number of miscarriages women experience) would be of great importance, dwarfing the scale of post-birth human welfare.22 On the other hand, an Epicurean view would render many traditional EA cause areas in global health comparatively unimportant. If death is not bad, then stopping people dying is less unambiguously good.23 This would mean, for example, that efforts to reduce the numbers of people dying from suicide, such as those by the EA-adjacent Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention, are not as beneficial or worthwhile as thought. The importance of other global health issues, like tackling malaria or increasing uptake of vaccines, would also be reduced: diseases would matter only due to them being sources of morbidity, not mortality. This conclusion would generalise to other morally-relevant species, too – under an Epicurean framework, animal welfare activists might want to focus on campaigning for industry to use more humane conditions and killing methods for livestock, rather than advocating a societal shift away from consumption of animal products.

Of course, human deaths do have wider costs: the passing on of a loved one causes much grief, anguish and suffering for those left behind. Even if one is not harmed by one’s own demise, death’s social disvalue is therefore an argument in favour of its importance as a welfare-affecting problem.

How good is life?

Deprivationism explains death’s badness by appealing to the lost goodness of life. If we assume (for the time being) that wellbeing is what tracks the goodness of a person’s life, then being alive is not in itself good, but rather a means of having positive welfare. There are three dominant theories about what constitutes wellbeing. Hedonism holds that only pleasure and pain truly matter in terms of value. Desire satisfaction argues that that the actual fulfilment of desires (e.g. a wish to have climbed Mount Everest) is what determines wellbeing.24 Finally, the objective list specifies particular goods that are believed to be necessary for wellbeing, above and beyond their direct impact on instantaneous pleasure (such as knowledge or friendship).25

Under any of these frameworks, the welfare gained from a year of life is not likely to be uniform: some years of life are much better than others. This variability is what metrics such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are designed to account for. QALYs or DALYs are favoured by governments26 and philanthropists27 as measures of cost-effectiveness over a crude “lives saved per dollar” calculation since if, like Ord, one rejects the Epicurean account of death, the welfare gains from averting a young person’s death are larger than those from doing the same for an elderly person. Moreover, QALYs and DALYs also take account of the different wellbeing levels that patients receiving treatment may end up at (capturing “healthspan”, rather than mere lifespan, to use the parlance).

To determine the improvement in quality of life that an intervention might bring, different health states need to be placed on a single numerical scale, after which the different options can be compared in terms of the QALYs gained per unit resource.28 The scale usually ranges from 0 to 1, representing death and full health respectively. However, as early as the 1970s, critics noted that taking death as the worst possible health state is a “questionable assumption in view of the occurrence of suicide, requests to withdraw from lifesaving procedures such as renal dialysis, the euthanasia debate and so on”.29 The surveying and statistical techniques used to produce QALY datasets allow researchers to identify health states (such as chronic unconsciousness) which the public perceive as worse than death.30 When people in these states are asked whether they believe their lives are worth continuing, though, the results indicate that they are not wholly dissatisfied with living.31 This discrepancy challenges the validity of QALYs as a measurement, at least in edge cases. Moreover, it seems unlikely that it would be possible to externally, objectively determine whether someone’s life is net-positive or net-negative.

At this stage, it seems useful to step back and consider the underlying purpose of QALYs as a measurement tool. They exist to help policymakers select interventions that bring the most health benefits per dollar, but a hedonist would argue that good health matters only insofar as it is instrumentally required for pleasure (I come on to consider other value systems shortly).32 From this perspective, QALYs and DALYs are merely proxies for individual welfare – approximators of “wellbeing-adjusted life years”, if you will.33 In a sense, this is rather like the objective list approach, specifying what matters for wellbeing in an attempt to externally determine an individual’s welfare. Both these approaches run the risk of being wrong about what people value. Why not follow the lead of Torrance (1984) and measure wellbeing directly by asking about it?

This approach, known as subjective wellbeing measurement, has gained traction in recent years, and within the EA community has been promoted by the Happier Lives Institute (HLI). Generally, this is done by asking respondents how satisfied they feel with their lives, in line with the desire satisfaction theory. Asking people how happy they feel at a given time would fall more under a hedonic methodology, and it is an open question as to which model of wellbeing is philosophically correct, as well as whether the question framing matters practically for results.34

An area of research that appears to have little exploration in the literature is how human cognitive biases shape our perceptions of wellbeing. The behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman introduced the distinction between our “experiencing self”, which lives in the moment, and our “narrating self”, which looks backwards at memories.35 Kahneman notes how what is good for one of these selves is not necessarily good for the other. Perhaps the best-known example of this divergence is the peak-end rule, wherein a person’s narrating self tends to judge an experience based on how they reported feeling at its most intense point and at its end, rather than as an average of their feelings over the entire experience. This has led to the discovery of phenomena such as people retrospectively preferring more drawn-out medical procedures to more intense, shorter ones, even if the number of pain-minutes was longer.36 The answer to the normative question of whether one ought to optimise for the experiencing self or the narrating self thus has practical implications. Focussing on the experiencing self might, for example, lead to a focus on technologies which alleviate pain – or in an extreme, the development of Robert Nozick’s experience machine, a hypothetical device which would fully immerse the user in perfectly pleasant simulated experiences, leaving them completely unaware of the outside world.37 Prioritising the narrating self, on the other hand, could plausibly leave more of a place for non-hedonic intrinsic goods which contribute to our narrative wellbeing and sense of life satisfaction. Several papers exploring the relationship between equality and happiness have found that periods of greater income inequality are associated with worse population wellbeing, due to a lower perceived level of societal fairness.38 However, this and similar research is largely irrelevant to those who hold the philosophical view that egalitarianism is intrinsically, as well as instrumentally, valuable: if you believe that equality matters in and of itself (a controversial view, particularly within the EA community), it matters little what the data show about its causal effect on wellbeing. To some extent, there is instrumental convergence between the hedonic (pleasure-focussed) and non-hedonic accounts of welfare, since many claimed non-hedonic intrinsic goods (like equality) are found to have empirical associations with measured levels of wellbeing. But knowing what is being maximised for, or at least reducing uncertainty around it, seems like an important goal: based on our current knowledge of determinants of wellbeing, a world optimised for equality of outcome would look very different to one optimised for self-reported happiness, for instance.

This appraisal of where value comes from has broader significance: selecting any flavour of welfarism over other consequentialist frameworks, let alone deontology or virtue ethics, matters greatly.39 The belief that, say, justice or honesty are valuable only instrumentally could plausibly lead to very different altruistic strategies than one where they are viewed as intrinsic goods distinctly valuable from wellbeing.40 At a practical level, choices around welfare frameworks can lead to differences in what interventions to prioritise. Work by HLI claimed that the mental health charity StrongMinds was nine times as cost-effective as the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF) in improving subjective wellbeing (as opposed to increasing QALYs, which HLI argues underweight the importance of mental health to welfare)41 – although it’s important to note that this analysis has been heavily disputed, and a subsequent shallow review by GiveWell estimated StrongMinds was only 25% as effective as their top charities.42 Nonetheless, the existence of a class of previously-neglected, worthwhile mental health interventions hinted at by these findings indicate that the assumptions behind how good is measured do matter, and that it is valuable to explore and interrogate them. Wherever non-hedonic intrinsic goods are claimed to exist, they may influence cost-effectiveness assessments. For example, a belief in the intrinsic value of individualism could also make organisations like GiveDirectly (which provide money that recipients in the developing world can then spend with no strings attached) relatively more cost-effective than charities which distribute products or services, like AMF – though, as far as I know, no detailed evaluations have been made of this.

How special are today’s humans?

Normative decisions are not only important for charity selection. Philosophical positions on longtermism also have a substantial impact on cause area prioritisation. Taking the view that individuals in the future have equal moral weight to those alive today would lead to one placing a far greater emphasis on the reduction of existential risk (x-risk), as opposed to causes focussed solely on improving the present-day world. In numerical terms, there are estimated to be around 100 trillion potential human lives found in the future.43 That means that, for instance, a 0.01 percentage point reduction in x-risk would be of roughly the same scale (in terms of expected lives saved) as averting the deaths of 90%44 of the world’s current population.

In their write-up of how to best apply the INT framework, 80,000 Hours highlights that “trade-offs across [different types of impact, like x-risk reduction, increases in QALYs, and economic growth] are very sensitive to big worldview and value judgements”. 45 Of course, the answers to these value judgements are not settled: longtermism is not necessarily correct, but prioritisation must be done all the same in spite of moral uncertainty.

In light of this, MacAskill and Ord, along with Krister Bykvist, propose a mental “moral parliament” to deal with such uncertainty. In this model, one allocates a number of imaginary delegates to represent different normative stances, proportional to the credence each is held with. When making decisions, all delegates first negotiate with each other on a “motion”, and then vote according to their moral framework to select a course of action.46 As the three highlight in Moral Uncertainty, obtaining more moral information is useful, because it allows us to make better-informed moral decisions by updating our parliament’s distribution of delegates – and as a result, “the expected choice-worthiness of engaging in further ethical reflection, study, or research can be very high”.47

An appreciation of the uncertainty we operate under is also useful as a means of avoiding naïve maximisation (which can be extremely damaging if the wrong goal is selected),48 and helpfully acts as a nudge towards pluralism and worldview diversification.49 This is why I believe that an understanding of the philosophical landscape is important: see the Appendix for an overview of three contentious issues in population ethics which would affect an individual’s credence in longtermism.

The non-identity problem is challenging to resolve because of the complications involved when comparing the value of worlds with different individuals in existence. For Lucretius, another ancient philosopher, non-existence was not a bad thing: he added to Epicurus’ arguments against the badness of death by suggesting a symmetry between our non-existence before birth – which he claims that nobody finds objectionable – and after death.50 Lucretius holds that existence and non-existence are so qualitatively different from one another that one cannot accurately be described as better than the other.51 This non-comparativist position is also promoted by McMahan, who notes that whilst “to cause a person to exist is good for that person when the intrinsically good elements of the person’s life more than compensate for the intrinsically bad elements”, it does not automatically follow that it is better for this person to be caused to exist. This is because betterness is only meaningful as a contrast to worseness: if existence is better for a person, then non-existence is worse. But, taking a person-affecting view, nothing can possibly be bad for a person who remains unborn; “people who never exist cannot be victims of misfortune”.52

If it is not unambiguously better for a person to exist than not to exist, then that could imply – for instance – that the instantaneous, painless extinction of humanity would not be a bad thing. Or, in a less bold but still significant claim (conceding that death may be bad for all those presently alive), it would imply that everyone collectively deciding to not have children and humanity thereby going extinct would harm nobody, and thus not be bad at all.

At a small scale, a mother may therefore wonder whether her giving birth was better for her child than her not having done so. Here, intuitions tend to point people towards what is known as the “procreation asymmetry”: that bringing a net-positive life into existence is a morally neutral act, but bringing a net-negative life into existence is a morally wrong act.53 At a larger scale, this contested claim challenges the notion that failing to create goodness is wrong, a tenet of longtermism. Put another way, is it right to be “neutral about creating happy people”?54 Using average or total utilitarianism sidesteps this issue, but for those who hold person-affecting views, it seems to me that the possibility of a value comparison between existence and non-existence (with existence as better) is essential for longtermism. Even within the EA community, there is considerable discussion and debate around this crux, and as a result, the importance of x-risk reduction as compared to other cause areas.55

Whilst a planet after human extinction would be a bleak one, it would not necessarily be devoid of moral worth. Some hold that the continued presence of organic life, and especially of other animals, would be meaningful, as these organisms also have moral relevance – and they are far more numerous than humans. Each year, there are around 3 billion mammals, 70 billion chickens, and 100 billion fish slaughtered for human consumption.56 Of course, these animals (and their suffering, if they do suffer) only exist as a result of human demand for meat. But even greater in number are wild animals: the ethicist and wild animal suffering researcher Brian Tomasik estimates there are somewhere between 10^11^ and 10^14^ noncaptive vertebrate animals and at least 10^18^ arthropods (a type of invertebrate including insects).57 For comparison, the current human population is around 10^10^.

This huge discrepancy in number of individuals means that, irrespective of one’s views on the relative moral significance of humans and non-human animals, it seems numerically unlikely that the weights applied happen to be such that the two cause areas appear as issues of similar magnitude. In other words, either human or non-human welfare would likely dwarf the other in scale, to the extent that the lesser cause would be irrelevant on the margin. Determining the “true” moral weights of different species would therefore be a significant step forward for cause prioritisation.

There have been attempts to operationalise these issues and move from abstract-level questions about moral weight to object-level ones. One approach, favoured by Tomasik, is to take the number of neurons found in the brains of different species as the basis for an approximation of their relative moral weights.58 However, this method has come under recent criticism from the EA research institute Rethink Priorities (RP), which argues that neuron counts are poor proxies for moral relevance and have only a tenuous connection to information processing capabilities, intelligence, or consciousness. Instead, RP suggests opting for “an overall weighted score that includes information about whether different species have welfare-relevant capacities”.59 But, deciding what constitutes a welfare-relevant capacity is ultimately a normative endeavour: although RP’s experimental work exploring other behavioural and cognitive hedonic proxies (including taste aversion, fear-like behaviour, and a concept of death) is informative and fills an important gap in the literature,60 descriptive information alone is not enough to assign species moral weights. Even when considering the most basic question of whether animal welfare matters at all, note how the only way to make a statement like “pigs have moral relevance” falsifiable is to define “moral relevance” in object-level terms. The trouble is, producing such a definition would itself be a moral undertaking.

Hume highlighted this type of tautology in his description of the is-ought problem. Also known as the fact-value distinction, this is the claim that moral conclusions cannot logically be inferred from non-moral factual premises. Hume’s brief discussion of the problem observed that “the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason”,61 and subsequent work by G. E. Moore similarly focussed on showing that goodness cannot be reduced to empirical observations.62 This distinction between facts and values can be generalised to the claim that one cannot validly move from descriptive statements to normative ones, which would fundamentally undermine efforts to objectively assign moral weights to different species, since it implies that moral value judgements must at some stage be introduced into the process.

It is worth emphasising that the is-ought problem does not imply that ethical introspection is pointless or meaningless. Whilst Hume was a sceptic and argued that moral beliefs were derived from axiomatic “sentiments”,63 a distinction between facts and values is still compatible with the argument that reflection on our moral beliefs helps us to improve them – you could consider there to be two parallel systems of reasoning, one seeking empirical truths, the other aimed at moral ones. Even for a moral anti-realist (one who believes that moral statements aren’t objectively true or false like factual statements are), there are strong reasons to engage in ethical introspection – most simply, because they must accept that, given moral uncertainty, there is a possibility that they are incorrect.64

Conclusion

This paper has shown that many cruxes about selecting one cause over another either boil down to differences in philosophical views or rest on implicit moral assumptions. Three particularly pertinent sets of questions revolve around the badness of death, goodness of life, and uniqueness of humans. As the variety of examples presented have demonstrated, one’s beliefs about these topics matter practically, and can lead to different causes or interventions being prioritised.

In light of this, and Hume’s convincing arguments that it is impossible to reach morally-grounded conclusions without morally-grounded premises, I think it’s important that EAs spend time actively forming their own views on philosophical issues as well as empirical ones. The memorable advice to “shut up and multiply” in order to avoid scope insensitivity only works if you know what’s inside of scope and what’s outside.65 Deciding whose welfare is morally relevant, and whose isn’t, is a philosophical question at heart. This unavoidability of philosophical dilemmas in cause prioritisation, and EA more generally, demonstrates the importance of considering such questions explicitly, rather than shying away from ethical arguments to rely exclusively on empirical findings.

Two notable counterarguments against the value of further philosophical reflection were raised: the claim that the opportunity cost of spending additional time on such work is unwarranted; and the suggestion that these questions are in any case intractable. In response to the first, I highlighted how changes in moral views can lead to orders-of-magnitude differences in the apparent importance of cause areas, illustrating the need for philosophical reflection before an individual hastily begins working directly on their chosen cause. As for the second objection, even if definitive answers are impossible to arrive at, Ord, MacAskill and Krister’s research on uncertainty demonstrates how refining and increasing confidence in our philosophical beliefs (something which is tractable) can enable us to make more moral decisions.

Reasoning transparency and epistemic legibility are core values of EA: they allow underlying areas of disagreement to be identified, leading to more productive discussions, and also help individuals to calibrate their confidence in their own conclusions. Good epistemic practices are important for philosophical questions as well as empirical ones. As this paper has argued, I think more people involved within EA could valuably spend time exploring and fleshing out their views on the former.

Appendix: three open debates in longtermism and population ethics

-

Whether or not “discounting” should be used when evaluating moral significance. Most mainstream economists would argue that a fractional multiplier should be applied to reduce the weight of future goods when performing cost-benefit analyses (potentially including the wellbeing of future people).66 The UK Treasury’s Green Book recommends a discount rate of 3.5% over the first 30 years of the future, and then a shrinking but still non-zero discount rate beyond that.67 It is widely accepted that some level of discounting may be justified, to account for factors such as the probability that future people are wealthier and more technologically advanced than today, the chance of a global catastrophic event occurring which leads to human extinction, and uncertainty about the future or our ability to influence it. To an extent, these economic, existential, and epistemic explanations are testable, empirical reasons to discount: growth can be modelled, x-risk can be estimated, historical precedent can be used to infer the future’s malleability from today. Moral motivations for discounting based on the claim that the wellbeing of future people simply matters less than ours are more contentious. Many within EA draw on the work of the philosopher Derek Parfit68 and economist Frank Ramsey69 to argue that this rate of “pure time discounting” should be zero, but the consensus intuition-driven view, as seen in the Green Book, is that the human preference for having goods sooner rather than later can be extrapolated to justify (or at least explain) pure time discounting, even between generations. From a philosophical standpoint, some have suggested that impossibility of reciprocity between us and individuals in the long-term future means that our distant descendants do not have rights or moral relevance, and that a high discount rate would be justified (though this argument may not be convincing to those who believe that moral patients such as animals have moral weight – as discussed in the next section).70 Even with the application of a nominally small discount rate of 0.1%, the net present value of the next thousand years would be greater than that of the following million years.71 Discounting can make the importance of the long-term future disappear.

-

Whether to use “average” or “total” utilitarianism, if adhering to impersonal utilitarianism. These refer to whether the moral value which matters is a population’s average welfare, or its total welfare. In addition to each method having its own challenging theoretical conclusions when pushed ad extremis (such as Parfit’s Repugnant Conclusion, which suggests that a world with a vast population experiencing only barely positive wellbeing is better than one where a smaller population experiences higher average wellbeing), selecting between the two positions also has practical effects. For instance, average utilitarianism might lead one to promote greater use of contraception and other population control measures (to avoid bringing below-average lives into existence), whereas total utilitarianism might cause one to view anti-abortion advocacy as a positively impactful cause area, effectively the opposite actionable conclusion.72

-

Whether to hold strong or weak person-affecting views, if not using the above utilitarian positions. Person-affecting views are a way of assessing the moral value of an action and assert that, in order to be described as harmful, an act must be bad for a particular person (strong/narrow form) or people in general (weak/wide form).73 If the narrower form is used, the so-called non-identity problem emerges, which posits that seemingly harmful actions which bring individuals into existence may not, in fact, be wrong.74 Towards the end of his life, Parfit proposed the “Wide Dual Principle”, which assess population scenarios based on both collective and individual wellbeing, as a means of avoiding the non-identity problem and the least appealing formulations of the Repugnant Conclusion. However, this principle also faces philosophical problems: in particular, whether individual and collective welfare can legitimately be traded off against one another.75 On the other hand, if we were to use an aggregated form of utilitarianism (such as one of the two outlined earlier), we would have no need for person-affecting views at all.76

Bibliography

80,000 Hours. n.d. Which global problem should you work on? Accessed March 31, 2023. https://80000hours.org/problem-quiz/.

Bader, Ralf M. 2022. “The Asymmetry.” In Ethics and Existence: The Legacy of Derek Parfit, edited by Jeff McMahan, Tim Campbell, James Goodrich and Ketan Ramakrishnan, 15-37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benatar, David. 2020. “Suicide Is Sometimes Rational and Morally Defensible.” In Exploring the Philosophy of Death and Dying, edited by Travis Timmerman and Michael Cholbi. New York: Routledge.

Bernfort, Lars, Björn Gerdle, Magnus Husberg, and Lars-Åke Levin. 2018. “People in states worse than dead according to the EQ-5D UK value set: would they rather be dead?” Quality of Life Research 1827-1833.

Broome, John. 2019. “The Badness of Dying Early.” In Saving People from the Harm of Death, edited by Espen Gamlund and Carl Tollef Solberg, 105-115. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burgess, David F., and Richard O. Zerbe. 2011. “Appropriate Discounting for Benefit-Cost Analysis.” Benefit-Cost Analysis 1-20

Carlsmith, Joe. 2021. Against neutrality about creating happy lives. 15 March. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/HGLK3igGprWQPHfAp/against-neutrality-about-creating-happy-lives.

Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention. n.d. FAQ. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://centrepsp.org/faq-2/.

Christiano, Paul. 2016. Integrity for consequentialists. 14 November. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/CfcvPBY9hdsenMHCr/integrity-for-consequentialists-1

Cohen, Alex. 2023. Assessment of Happier Lives Institute’s Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of StrongMinds. 22 March. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/h5sJepiwGZLbK476N/assessment-of-happier-lives-institute-s-cost-effectiveness

Cotton-Barratt, Owen, and Daniel Kokotajlo. 2015. How can we help the world? A flowchart. 2 September. Accessed March 31, 2023. http://globalprioritiesproject.org/2015/09/flowhart/.

Crisp, Roger. 2021. Well-Being. 27 October. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/well-being.

De Brigard, Felipe. 2010. “If you like it, does it matter if it's real?” Philosophical Psychology 43-57.

Derek. 2020. Health and happiness research topics—Part 1: Background on QALYs and DALYs. 9 December. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/Lncdn3tXi2aRt56k5/health-and-happiness-research-topics-part-1-background-on.

Duda, Roman. 2022. Global priorities research. November. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://80000hours.org/problem-profiles/global-priorities-research/#1-some-problems-are-far-more-pressing-than-others.

Dullaghan, Neil. 2019. EA Survey 2019 Series: Community Demographics & Characteristics. 5 December. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/wtQ3XCL35uxjXpwjE/ea-survey-2019-series-community-demographics-and.

Duncan, Peter. 2010. “Health, health care and the problem of intrinsic value.” Evaluation in Clinical Practice 318-322.

Feldman, Fred. 1991. “Some Puzzles About the Evil of Death.” The Philosophical Review 205-227.

Fischer, Bob. 2022. The Welfare Range Table. 7 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/y5n47MfgrKvTLE3pw/p/tnSg6o7crcHFLc395.

Giving What We Can. n.d. Our history. Accessed March 2023, 30. https://www.givingwhatwecan.org/about-us/history.

Greaves, Hilary. 2019. “Against the "Badness of Death".” In Saving People from the Harm of Death, edited by Espen Gamlund and Carl Tollef Solberg, 189-202. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hazell, Julian. 2022. The perils of underestimating second-order effects. 11 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://muddyclothes.substack.com/p/the-perils-of-underestimating-second.

Hume, David. 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature. London: John Noone.

Joyce, Richard. 2022. Moral Anti-Realism. 10 December. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/moral-anti-realism.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Jason Riis. 2005. “Living, and thinking about it: two perspectives on life.” In The Science of Well-Being , edited by Felicia A. Huppert, Nick Baylis and Barry Keverne, 284-305. Oxford: Oxford Academic.

Kahneman, Daniel, Barbara L. Fredrickson, Charles A. Schreiber, and and Donald A. Redelmeier. 1993. “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End.” Psychological Science 401-405.

Karnofsky, Holden. 2022. EA is about maximization, and maximization is perilous. 2 September. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/T975ydo3mx8onH3iS/ea-is-about-maximization-and-maximization-is-perilous.

—. 2016. Worldview Diversification. 13 December. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/worldview-diversification/.

Lowe, Joseph. 2008. “Intergenerational wealth transfers and social discounting: Supplementary Green Book guidance.” HM Treasury. July. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/193938/Green_Book_supplementary_guidance_intergenerational_wealth_transfers_and_social_discounting.pdf.

Luper, Steven. 2021. Death. 14 September. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/death.

MacAskill, William. 2020. Twitter. 10 September. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://twitter.com/willmacaskill/status/1304075463455838209.

MacAskill, William, Krister Bykvist, and Toby Ord. 2020. “Moral Information .” In Moral Uncertainty, by William MacAskill, Krister Bykvist and Toby Ord, 197-210. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Malde, Jack. 2021. Important Between-Cause Considerations: things every EA should know about. 28 January. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/4vcccwaBJwQcRr7Lp/important-between-cause-considerations-things-every-ea.

—. 2020. The problem with person-affecting views. 5 August. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/HyeTgKBv7DjZYjcQT/the-problem-with-person-affecting-views.

Masny, Michal. 2020. “On Parfit’s Wide Dual Person-Affecting Principle .” The Philosophical Quarterly 114-139.

McGuire, Joel, Samuel Dupret, and Michael Plant. 2022. Happiness for the whole household: accounting for household spillovers when comparing the cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy to cash transfers. 14 April. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zCD98wpPt3km8aRGo/happiness-for-the-whole-household-accounting-for-household.

McMahan, Jeff. 2013. “Causing People to Exist and Saving People’s Lives.” The Journal of Ethics 5-35.

Meyer, Lukas. 2021. Intergenerational Justice. 4 May. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/justice-intergenerational.

Moore, G. E.. 1903. Principia Ethica. Cambridge: University Press.

Moorhouse, Fin, Michael Plant, and Tom Houlden. 2020. The philosophy of wellbeing. Happier Lives Institute. https://www.happierlivesinstitute.org/report/the-philosophy-of-wellbeing.

Moss, David. 2021. EA Survey 2020: Cause Prioritization. 29 July. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/YLudF7wvkjALvAgni/p/83tEL2sHDTiWR6nwo.

Muehlhauser, Luke. 2013. Fermi Estimates. 11 April. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/PsEppdvgRisz5xAHG/fermi-estimates.

Narveson, Jan. 1967. “Utilitarianism and New Generations.” Mind 62-72.

Nichols, Peter. 2012. “Abortion, Time-Relative Interests, and Futures Like Ours”. Ethic Theory Moral Prac 493-506.

Newberry, Toby and Toby Ord. 2021. “The Parliamentary Approach to Moral Uncertainty”. Technical Report #2021-2, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford.

Oishi, Shigehiro, Selin Kesebir, and Ed Diener. 2011. “Income inequality and happiness.” Psychological Science 1095-1100.

Ord, Toby. 2020. The Precipice. London: Bloomsbury.

Ord, Toby. 2008. “The Scourge: Moral Implications of Natural Embryo Loss.” The American Journal of Bioethics 12-19.

Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban, and Max Roser. 2017. Happiness and Life Satisfaction. May. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction.

Özden, James. 2022. What you prioritise is mostly moral intuition. 24 December. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/CycFBmdwgCjCsZxQh/what-you-prioritise-is-mostly-moral-intuition.

Parfit, Derek. 1984. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parfit, Derek. 2016. The non-identity problem. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/YpjXuZkwzSnJxWE5h/transcript-of-a-talk-on-the-non-identity-problem-by-derek.

Plant, Michael, Olivia Larsen, Jason Schukraft, Matt Lerner, and Katrina Sill. 2022. Measuring Good Better. 14 October. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/8whqn2GrJfvTjhov6/measuring-good-better-1.

Ramsey, F. P. 1928. “A Mathematical Theory of Saving.” The Economic Journal 543-559.

Roberts, M. A. 2022. The Nonidentity Problem. 28 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/nonidentity-problem.

Roser, Max. 2022. Longtermism: The future is vast – what does this mean for our own life? 15 March. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/longtermism.

Rosser, Rachel, and Paul Kind. 1978. “A Scale of Valuations of States of Illness: is there a Social Consensus?” International Journal of Epidemiology 347-358.

saulius. 2020. Estimates of global captive vertebrate numbers. 18 February. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/pT7AYJdaRp6ZdYfny/estimates-of-global-captive-vertebrate-numbers.

Schubert, Stefan, and Lucius Caviola. 2021. “Virtues for Real-World Utilitarians.” PsyArXiv. https://psyarxiv.com/w52zm.

Shriver, Adam. 2022. Why Neuron Counts Shouldn't Be Used as Proxies for Moral Weight. 28 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/Mfq7KxQRvkeLnJvoB/why-neuron-counts-shouldn-t-be-used-as-proxies-for-moral.

Simnegar, Ariel. 2022. A Case for Voluntary Abortion Reduction. 20 December. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/6ma8rxrfYs3njyQZn/a-case-for-voluntary-abortion-reduction.

Simon_M. 2022. StrongMinds should not be a top-rated charity (yet). 27 December. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ffmbLCzJctLac3rDu/strongminds-should-not-be-a-top-rated-charity-yet.

Singer, Peter. 2009. The Life You Can Save. London: Picador.

Todd, Benjamin. 2015. We care about WALYs not QALYs. 13 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/nevDBjuCPMCuaoMYT/we-care-about-walys-not-qalys.

Tomasik, Brian. 2019. How Many Wild Animals Are There? 7 August. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://reducing-suffering.org/how-many-wild-animals-are-there/.

—. 2018. Summary of My Beliefs and Values on Big Questions. 6 February. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://reducing-suffering.org/summary-beliefs-values-big-questions.

Torrance, G. W. 1984. “Health States Worse than Death.” Third International Conference on System Science in Health Care 1085-1089.

Weiler, Sarah. 2022. Cruxes for nuclear risk reduction efforts - A proposal. 16 November. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/pqGnC4sAjzzZHoqXY/cruxes-for-nuclear-risk-reduction-efforts-a-proposal.

Wiblin, Robert. 2019. A framework for comparing global problems in terms of expected impact. October. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://80000hours.org/articles/problem-framework.

York Health Economics Consortium. 2016. Standard Gamble. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://yhec.co.uk/glossary/standard-gamble/.

—. 2016. Time Trade-Off. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://yhec.co.uk/glossary/time-trade-off/.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. 2008. Circular Altruism. 22 January. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/4ZzefKQwAtMo5yp99/circular-altruism.

-

Giving What We Can n.d. ↩︎

-

Dullaghan 2019. Note that these are the most recent data available, but the growing importance assigned to AI safety as a cause area since 2019 (Moss 2021) seems like it would lead to a continuation or acceleration of the trend that EA is increasingly made up of STEM rather than philosophy graduates. ↩︎

-

Duda 2022 ↩︎

-

Malde 2021 ↩︎

-

Duda 2022 ↩︎

-

Malde 2021 ↩︎

-

Joyce 2022 ↩︎

-

MacAskill 2020 ↩︎

-

Muehlhauser 2013 ↩︎

-

Perhaps, for example, the St. Petersburg Paradox, or extreme thought experiments in population ethics like the Very Repugnant Conclusion – though these too seem like they could be important considerations when selecting a value system. ↩︎

-

See, for instance, Schubert and Caviola 2021; Christiano 2016 ↩︎

-

Özden 2022 ↩︎

-

Singer 2009, 19 ↩︎

-

Luper 2021 ↩︎

-

Ord 2020, 48 ↩︎

-

The deprivationist argument relies on either an ability to evaluate moral propositions at any point in time, meaning that someone’s impending death is bad for them immediately before they die and cease to exist, or on the goodness of things being impersonal, and not needing reference to a specific individual they benefit or harm. These ideas are explored more in the next section. ↩︎

-

Feldman 1991 ↩︎

-

McMahan 2002, 171 ↩︎

-

One example presented is of a doctor choosing whether to save the life of a 2-year-old, given that she would die aged 15 (but live a valuable life in the 13-year interim). Intuitively, we conclude that the doctor clearly should save the patient’s life, but TRIA would suggest that her death aged 15 is worse for her than one as an infant, and so the doctor ought to think twice. McMahan claims that TRIA does lead to the desired conclusion here, though admits it is “paradoxical” it recommends a course of action leading to a worse death for the patient. Greaves goes on to discuss further adversarial thought experiments which pose greater challenges to TRIA. ↩︎

-

McMahan 2002, 360 ↩︎

-

Plant, et al. 2022 ↩︎

-

Ord 2008 ↩︎

-

The ethics of suicide and suicide prevention are complex, fraught and emotionally charged, and there is not space to do full justice to them here. CPSP argues that a “high proportion of pesticide suicides are impulsive” (Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention n.d.), supported by data showing that after the ban of highly hazardous pesticides in Sri Lanka, the overall suicide rate fell by 75% i.e., the removal of these toxic chemicals as a potential method of suicide did not merely displace desperate people to other means. However, there are philosophers who hold that suicide can, sometimes, be the rational course of action, a view which I find convincing – if extremely uncomfortable – and which is discussed more in the next section (Benatar 2020). It may be that dying from the consumption of toxic pesticides is an especially awful experience, and therefore that preventing anyone having to go through this would be beneficial. But the same would not necessarily be true for all suicides – consider, for example, our hypothetical button earlier, where no pain would be experienced. ↩︎

-

Moorhouse, Plant and Houlden 2020 ↩︎

-

Crisp 2021. In a more quantifiable sense, this might look something like the Human Development Index, which combines metrics on health, standard of living, and education, to produce an overall wellbeing-like score. ↩︎

-

Derek 2020 ↩︎

-

The metrics are common enough within EA that they each have their own parody Twitter accounts. ↩︎

-

The conversion of health states to a numerical value is typically done with a technique known as the Standard Gamble. The method involves surveying a sample of people, who are presented with a choice between a certain outcome, where they remain in a specific health state say, with short-sightedness for a certain number of years, and a gamble in which they might either a live in full health for the same number of years or b die immediately. The chance of immediate death in the second scenario is then changed accordingly, until the person is indifferent between the two options. The final probability indicates the relationship between the specific health state and full health: if they were indifferent at a 2% chance of survival, then for that person, a year spent in the short-sighted health state is 98% as valuable as one spent in full health (York Health Economics Consortium 2016). Alternatively, a method known as “Time Trade Off” may be used; this also determines the point of equivalence between a specific health state and full health, but does so by finding the value of the ratio of remaining years of life spent in full health : remaining years of life spent in health state at which the respondent is indifferent between the options (Ibid). ↩︎

-

Rosser and Kind 1978 ↩︎

-

Torrance 1984 ↩︎

-

Bernfort, et al. 2018 ↩︎

-

Duncan 2010 ↩︎

-

Todd 2015 ↩︎

-

Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2017 ↩︎

-

Kahneman and Riis 2005 ↩︎

-

Kahneman, Fredrickson, et al. 1993 ↩︎

-

Nozick used the thought experiment to argue against hedonism, claiming that people would choose not to plug themselves in to the machine, and that this demonstrates that other things matter to us besides pleasure. However, some more recent studies which adjusted the scenario’s formulation to avoid the effects of status quo bias. De Brigard (2010) found that people would in fact prefer the simulated reality or at least, would not opt to leave it for the real world, if they were to start out in the machine. ↩︎

-

Oishi, Kesebir and Diener 2011 ↩︎

-

Consequentialism is a theory that judges the morality of an action based on its outcomes or consequences, whilst deontology emphasises the inherent rightness or wrongness of actions, irrespective of their consequences. Virtue ethics is a third approach that focuses on individuals cultivating and embodying virtuous character traits which will ultimately lead to ethical decision-making. ↩︎

-

Though Hazell (2022) argues that after proper consideration of second- and higher-order effects, the difference between welfarism and other frameworks is slight. ↩︎

-

McGuire, Dupret and Plant 2022 ↩︎

-

Cohen 2023. See also Simon_M 2022. ↩︎

-

If humanity survives for another 800,000 years reaching a million years total, the average length of a typical mammalian species' existence, with a stable population of roughly 11 billion (Roser 2022). ↩︎

-

Not 100% of the global population, because although the number of people directly affected by this would be the same order of magnitude, the deaths of the final 10% of humans (or whatever proportion which would push numbers below the minimum viable population) would necessitate human extinction, and therefore also the loss of all future potential. ↩︎

-

Wiblin 2019 ↩︎

-

Any number of voting methods can be used within the moral parliament, including plurality voting (the choice with the most votes is always selected) or proportional chances voting (each option has a chance of being selected proportional to its share of the votes). Note that this parliamentary approach is subtly different to computing the expected payoffs from each action as a weighted sum of their payoffs under each moral framework (much like how one might make decisions under empirical uncertainty using expected utility), because it avoids the challenges that come with making comparisons about the value of actions between entirely different moral frameworks (e.g. utilitarianism and deontology). See Newberry and Ord 2021 for further discussion. ↩︎

-

MacAskill, Bykvist and Ord 2020 ↩︎

-

Karnofsky 2022 ↩︎

-

Karnofsky 2016 ↩︎

-

Luper 2021 ↩︎

-

Readers familiar with claimed proofs of God may have come across St. Anselm’s assertion, in his ontological argument, that existence is necessarily better than non-existence. Amongst Immanuel Kant’s critiques of the argument was that existence is not a property of an object, but rather a precondition for something to have properties – and therefore, that existence cannot be said to be better than non-existence. ↩︎

-

McMahan 2013 ↩︎

-

Bader 2022 ↩︎

-

Narveson 1967 ↩︎

-

Carlsmith 2021 ↩︎

-

saulius 2020 ↩︎

-

Tomasik 2019 ↩︎

-

Tomasik 2018 ↩︎

-

Shriver 2022 ↩︎

-

Fischer 2022 ↩︎

-

Hume 1739, 335 ↩︎

-

Moore 1903. In particular, Moore’s “Open Question Argument” and subsequent, more robust reformulations challenged this so-called “naturalistic fallacy”, essentially stating that it is always an open question whether a thing is good or not, regardless of whether it has material properties such as being pleasant or desirable – and that this demonstrates that goodness cannot be explained solely in terms of empirical observations. ↩︎

-

Hume 1739, 458 ↩︎

-

Carlsmith 2023 ↩︎

-

Yudkowsky 2008 ↩︎

-

Burgess and Zerbe 2011 ↩︎

-

Lowe 2008 ↩︎

-

Parfit 1984, 486 ↩︎

-

Ramsey 1928 ↩︎

-

Meyer 2021 ↩︎

-

For a geometric sequence $u_{n} = ar^{n - 1}$, the sum $S_{n} = \sum_{i = 1}^{n}{ar^{i - 1} = a\frac{1 - r^{n}}{1 - r}}$. In this case, $r = 1 - 0.001 = 0.999$, and the choice of $a$ is arbitrary. Taking $u_{1} = a = 1$, then $u_{10,000} = 0.368$. We can see that $S_{1,000} = 632$ and $S_{1,001,000} - S_{1,000} = 368$, so the net present value of the next thousand years is indeed greater than that of the following million. ↩︎

-

Simnegar 2022 ↩︎

-

Parfit 2016 ↩︎

-

One typical example is the building of a coal-fired power station in a town: its construction harms those living nearby in future, from the pollution and carbon emissions it will produce, but the town’s population could not have grown and included those individuals had the station not been built, so its construction cannot have been bad for those people. See Roberts 2022 for more complex and detailed thought experiments. ↩︎

-

Masny 2020 ↩︎

-

Malde 2020 ↩︎